Our Current Proposal

UNSC Reform is possible

Elect the Council is an international initiative to create an effective, legitimate and representative UN Security Council (UNSC) suited to the challenges of the 21st century. This is a summary of our proposal, which is detailed and specific, since this is an issue where ‘in principle’ support for reform often flounders on disagreement on the detail.

Introduction

There have been many attempts to reform the UNSC. None has been successful, other than the enlargement of the non-permanent category of members in 1965. There is no prospect for progress in the ongoing intergovernmental negotiations process under the auspices of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in New York. The negotiations are stuck between irreconcilable national positions as each country and group fights for national advantage. Many states hide behind this impasse, comfortable with the status quo.

In the meanwhile, the world is seeing changes in the distribution of power among states, and the empowerment of civil society organisations and business. Global governance systems are evolving but the UNSC remains ossified, despite threats such as the impact of climate change, nuclear terrorism, pandemics and organised crime. These threats are increasingly multidimensional and transnational, and threaten all of humanity.

The current composition of the UNSC is incapable of accommodating these realities. The lack of legitimacy of the UNSC translates into an inability to reform the rest of the UN system, and the steady attrition of its effectiveness.

Instead of seeking a middle ground where the national interests of key states converge, Elect the Council steps outside of the deadlock in the intergovernmental negotiations. Since early 2015 we have consulted widely with states, think tanks and civil society groups globally to hone a set of detailed proposals that reflect emerging power dynamics and build upon the 80-year legacy of the current council. These proposals also draw upon a significant body of long-term forecasting work done by the fut (ISS) and others.

An effective international governance system requires a reformed UNSC that reflects shifts in global geopolitical power. Not all states can contribute equally to global peace and security, but greater and more equitable global representation remains crucial.

At the heart of our approach is the need to move from a competitive system based on national interests to a collaborative and principle-based approach to the management of global security in an interdependent world. We see the UNSC as continuing to manage global peace and security issues, in coordination with regional organisations where appropriate, but also able to take preventive and remedial action based on its greater legitimacy and authority. This is, however, likely to be a less interventionist council.

The approach and conclusions of Elect the Council’s proposals is summarized in items 1 to 12 below:

Minimum Criteria for Global Powers and Coalitions of States

Not all states can shoulder the same responsibilities in relation to global peace and security. A future UNSC needs to be flexible while reflecting the emerging distribution of power. Long-term forecasts of power indicate a three-tiered global structure consisting of two eventually three) global powers (the United States [US], China and then India) with a large gap between these three and other states such as Brazil, Indonesia, Korea, Japan, Turkey, Russia, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK), France, etc. Most states are much lower down in the power stakes, constituting a third cluster. Elect the Council takes the view that the top tier of global powers must be included in a reformed UNSC. A council without them could be ignored or bypassed. The proposal therefore provides for a category of states that each have 3% of global population and 5% of global gross domestic product (at MER) and which contribute 5% of the UN budget, to automatically qualify to serve on the council while meeting all three criteria.

In addition, coalitions of states that collectively meet these criteria could also apply for a global powers seat. These states/coalitions would have enhanced voting powers in the council in that each of their votes would count for three, but they would lose their membership in the electoral regions that currently nominate the non-permanent members for election in the UNGA. They would also not be allowed to vote in the UNGA during the election of other states to the UNSC.

Renewable Terms for Regional Powers

In a complex world, the UN is increasingly working with and through regional organisations and relies on regional powers to play an important role in their respective geographical space. The proposal therefore provides for a category of regional powers, consisting of states that are elected to serve on the UNSC for an immediately renewable term of three years. Each of the electoral regions that currently nominate the non-permanent members of the UNSC would nominate one regional state for every 22 (rounded off) members. Actual elections would occur as normal within the UNGA (without the participation of global powers/members of global coalitions).

A third category of 16 rotational seats completes the composition of the council. Each region would be entitled to elect two states to the UNSC for every 22 (rounded off) members. These seats would not be immediately renewable and states would serve for a three-year term. Global powers and members of global coalitions would also not be allowed to vote in the election of the rotational seats. In this manner, the reformed council would ensure proportional representation of all regions on an equitable basis. Together with the other two categories of seats, a reformed UNSC would therefore consist of 24 elected countries plus two or three global powers or global coalitions.

Non-renewable Rotational Seats

Transition period of 18 years

No state would have a permanent seat on the UNSC, and the move to a new configuration would occur over a phased 18-year period. This would mean that the composition and working of the UNSC would follow the unfolding shifts in global power distribution. During the 18-year interim period the current P5 would remain members of the council with enhanced voting rights, but no veto. The council would additionally consist of 16 states elected for non-renewable three-year terms (as set out earlier) and five states elected for renewable three-year terms. This is because three of the P5 (China, the UK/France and Russia) already serve in three respective electoral regions. After the interim period the number of states elected for renewable three-year terms would increase from five to eight.

The UNSC is the only executive and legislative body entrusted with ensuring international peace and security. States that serve on the council should therefore have the resources, experience and global representation to make a meaningful contribution to peace and security. To this end we propose four minimum requirements. We believe that these criteria are best left to the geographical regions to apply in determining nominations for elections within the UNGA. The criteria are:

- Experience and capacity

- Financial good standing with the UN and its agencies

- Willingness to shoulder additional financial contributions to UN efforts on international peace and security, as determined by the UNGA

- Respect for open, inclusive and accountable governance, the rule of law, international law and international human rights standards

Electoral Regions to apply Eligibility Requirements

Voting for Rotational Seats in UNGA

Similar to current arrangements, electoral regions would nominate states for the 24 elected seats, but actual voting would occur within the UNGA. This arrangement would allow each region to manage its electoral processes according to its own preferences.

By adopting a system of proportional representation an expanded council would more equitably represent different regions, and would restore the legitimacy of the UN and the UNSC. The category of elected regional powers for renewable three-year terms should help change the dynamic between regional powers and other states in the same electoral college. The proposals would not be affected by changes to the composition of the current geographical regions, or by the establishment of cross-regional groups to accommodate the interests of groups such as the Arab Group and Small Island and Development States (SIDS).

Proportional Representation

More votes for Global Powers/Coalitions

It is important to create incentives for the P5 to change. In a reformed council, the vote of all elected states would count for one while the vote of global powers/coalitions would each count for three. During the 18-year transition period the votes of the P5 would initially each count for five (years 1 to 6), then four (years 7 to 12) and eventually three (years 13 to 18).

There are many obstacles that could impede progress. We propose that the current UNSC define up to five specific issues that should not attract additional Chapter VII resolutions for a period of 20 years after the adoption of the enabling UNGA resolution to amend the UN Charter, Change to, beyond updates, removal, maintenance or termination of existing decisions.

Five issues parked for 20 years

Mandatory Review every 30 years

The establishment of a regular review process of the UNSC would create the opportunity for future improvements and avoid a recurrence of the current impasse. A mandatory periodic review of the UNSC every 30 years would therefore be included in the UNGA resolution to amend the UN Charter.

In all of the above, the UN Charter would include provisions to ensure the council is not held hostage to procedure by a handful of its members. In this manner, outstanding issues such as the finalisation of the rules of procedure (which are still provisional) should be able to proceed apace. The UNGA and the International Court of Justice would serve to break procedural deadlocks as appropriate.

Deadlocks, UNGA and International Court of Justice

All in a Single Amendment to the UN Charter

These proposals would be contained in a single amendment to the UN Charter.

Conclusion

The proposals set out here differ fundamentally from the efforts to find an approach that could appease the P5, as well as aspirants to additional permanent or semi-permanent seats and groupings opposed to any enlargement of the permanent category of seats.

It is important to address the incentives to change for different countries and groupings. What possible motivations would lead the P5 or others to move from their current positions? We offer four compelling reasons.

The first relates to the need for a legitimate and effective global security management system for a hot, crowded and interdependent world facing multiple challenges, from climate change and migration to nuclear terrorism and pandemics.

The second is the need to unlock reform across the entire UN system. The role of the P5 in the UNSC serves as a blockage in an unwieldy UN structure that has become ineffectual and costly.

A third motivation is the extent of frustration with the lack of progress. A large number of countries are increasingly convinced that only a step-change in the approach to reform can unlock the current impasse. Elect the Council’s proposals offer such an opportunity.

Finally, in the case of the US, China and eventually India, these proposals provide a legitimate and fair recognition of their considerable global influence without repeating the challenges of permanency. Europe, which has benefitted from over-representation on the council for many decades, inevitably needs to accept a more proportional global role, but can retain influence by opting for a collective global powers seat. All regions will benefit from the move towards a proportional system.

GET INFORMED AND INVOLVED

Subscribe to our newsletter today to keep abreast of our initiatives to bring about the reform of the United Nations Security Council.

More from the UNSC Reform Blog

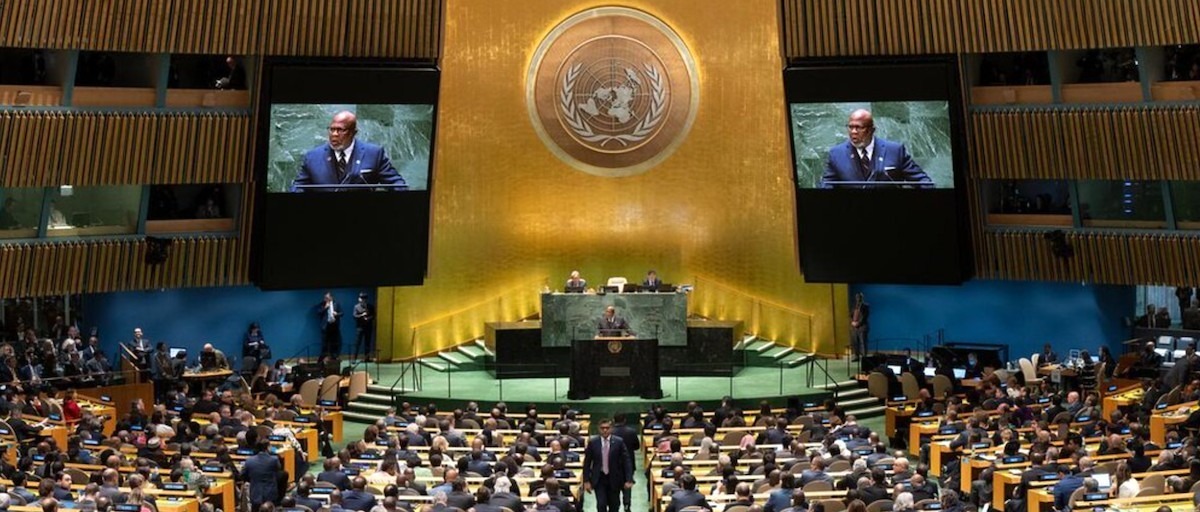

Going nowhere slowly at the UN General Assembly’s annual debate

At this critical juncture in world affairs, the general debate should have featured more solutions and better leadership.

AU plunges into turbulent G20

The African Union (AU) will likely be admitted as a permanent member of the G20 at the latter’s summit in New Delhi this weekend. To date, the AU has only attended summits of the G20 – the world’s foremost club for addressing global issues – as a guest. The G20…

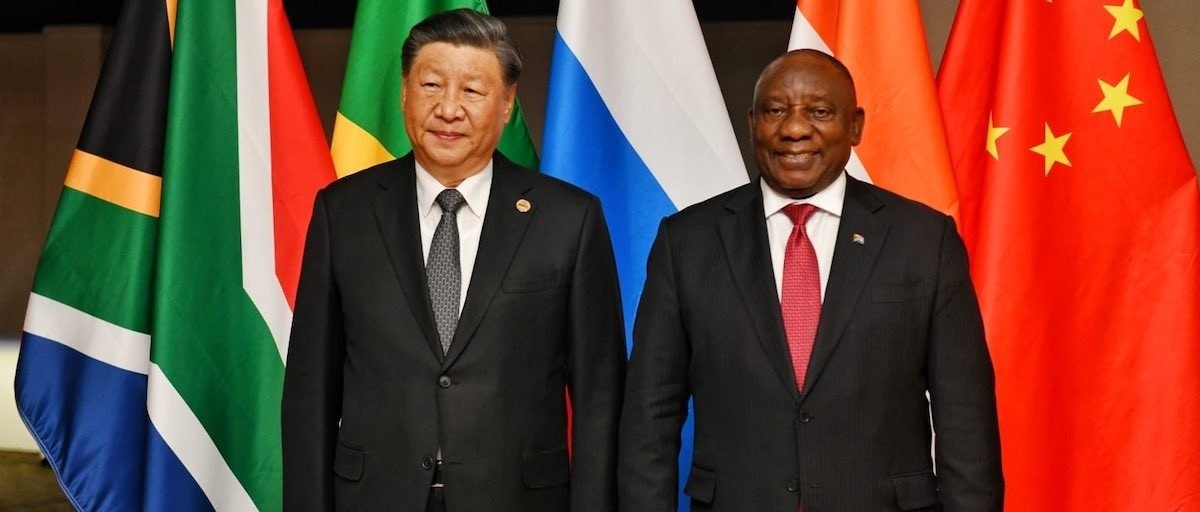

BRICS+ and the tricky business of balancing global geopolitics

Will an expanded BRICS precipitate a new international order, or collapse under the weight of its internal contradictions?

BRICS+ and the future of the US dollar

Although no single alternative to the dollar is likely, the shift away from a Western-led global order has begun.

Whose tune will an expanded BRICS dance to?

Will the inclusion of six new members in BRICS last week strengthen multipolarity or bipolarity?

What Africa wants and what the West needs to do

Democracy generally follows development, so Africa’s friends should focus on unlocking rapid growth through better governance.

How the Ukraine war ends, and implications for Africa

Four global scenarios capturing all reasonable outcomes show why rapprochement between the West and China is vital.

Russia’s war in Ukraine revives calls for Security Council expansion

The council was conceived in warfare – could that also bring reform, including adding a seat for Africa?

Africa has a rare chance to shape the international order

As global powers seek support for their competing worldviews, will Africa capitalise on its rising strategic value?

Zelensky’s adapt or die message should spur Security Council reform

United Nations’ impotence over Ukraine makes the case for ending the power of five countries to determine global security.